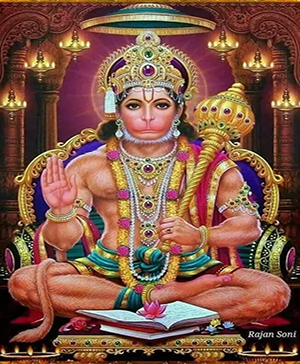

Lord Hanuman Puja

About Puja

Lakshmi Devi is always depicted sitting or standing on a lotus with golden coins flowing in an endless stream from one of her hands symbolic of when the lotus of wisdom blossoms, the wealth of good and noble qualities appears and Lakshmi's blessings are present. She is described as restless, whimsical yet maternal, with her arms raised to bless and to grant.

For centuries Hindus have invoked her thus:

Beautiful goddess seated on a chariot, Delighted by songs on lustful elephants, Bedecked with lotuses, pearls and gems,

Lustrous as fire, radiant as gold, Resplendent as the sun, calm as the moon, Mistress of cows and horses —

Take away poverty and misfortune Bring joy, riches, harvest and children.

The world may have changed, but the thirst for material comfort continues to form the core of most human aspirations.

The mythology of Lakshmi acquired full form in the Puranas, chronicles of gods, kings and sages that were compiled between 500 and 1500 AD. In them, the goddess came to be projected as one of the three primary forms of the supreme mother-goddess, the other two being Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, and Kali or Durga, the goddess of power. Lakshmi was visualised both as an independent goddess and as Vishnu’s consort, seated on his lap or at his feet. Prithvi, the Vedic earth-goddess, became Bhoodevi in the Puranas and a manifestation of Lakshmi. In south India, the two goddesses were visualised as two different entities, standing on either side of Vishnu, Bhoodevi representing tangible wealth while Lakshmi or Shridevi representing intangible wealth. In north India, the two goddesses became one.

Images of Lakshmi started appearing around the third century BC in sculptures found in Kausambi, in north India, and on coins issued during the reign of the Gupta dynasty around the fourth century AD. She became a favourite of kings as more and more people believed she was the bestower of power, wealth and sovereignty. Separate shrines to Lakshmi within the precincts of Vishnu temples may have been built as early as the seventh century; such shrines were definitely in existence by the 10th century AD.

ickle and independent

Nowadays, Hindus accept Lakshmi as the eternal consort of Vishnu, the preserver of the world. In her long history, however, the goddess has been associated with many other deities. According to Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas, the goddess Lakshmi first lived with the demons before the gods acquired her. She graced asuras such as Hiranayaksha, Hiranakashipu, Prahalad, Virochana and Bali, rakshasas such as Ravana and yakshas such as Kubera before she adorned the court of Indra, king of devas, the most renowned of Vedic gods. Cities of the asuras (Hiranyapura), yakshas (Alakapuri), rakshasas (Lanka) and nagas (Bhogavati) have all been described as cities of gold, Lakshmi’s mineral manifestation. Within the Vedic pantheon, Lakshmi was linked with many gods, especially those associated with water bodies: Indra, the rain-god (bestower of fresh water); Varuna, the sea-god (source of all water); Soma, the moon-god (waxer and waner of tides). Indra’s wife Sachi was also known as Puloma, which is the name of an asura-woman suggesting entry of Lakshmi from the world of asuras into world of devas.

As the Vedic gods waned into insignificance around the fifth century BC, two gods came to dominate the classical Hindu worldview: the world renouncing hermit-god Shiva and the world affirming warrior-god Vishnu. Lakshmi was briefly associated with Shiva before she became the faithful consort of Vishnu-Narayana, the ultimate refuge of man. With Vishnu, she was domesticated. No longer fleet footed, she sat demurely by his side, on his lap or at his feet.

The association with many gods has led to Lakshmi being viewed as fickle, restless and independent. Sociologists view the mythology of Lakshmi’s fickleness as indicative of her cult’s resistance to being assimilated with mainstream Hinduism. Even today there is tension between the mythology of Lakshmi as an independent goddess and her mythology as Vishnu’s consort. Philosophers choose to view the fickleness and independence of Lakshmi as an allegory for the restlessness of fortune. More often than not, there are no rational explanations for fortune and misfortune. Good times come without warning and leave as suddenly.